Set up to bring greater attention to contemporary poetry, the Forward prize celebrated its 20th anniversary this week. Fellow poets and writers pay tribute to those who have won the Best Collection.

Set up to bring greater attention to contemporary poetry, the Forward prize celebrated its 20th anniversary this week. Fellow poets and writers pay tribute to those who have won the Best Collection.

Blake Morrison on The Man With Night Sweats by Thom Gunn, 1992

“I wake up cold,” the title poem begins, “I who / Prospered through dreams of heat.” That sudden chill sets the tone for this collection of elegies, written at the height of the Aids epidemic. Gunn’s previous book, The Passages of Joy, 10 years before, had sung of the Californian good life: “Sweet things. Sweet things.” Desire for young flesh (“the hard-filled lean body”) still courses through this collection. But it’s chastened by grief and loss. The titles alone tell the story – “In Time of Plague”, “Terminals”, “The Missing”, “Lament” – and much of the imagery comes from the sickbed: greyish-yellow skin, pills, feeding tubes, parched mouths, collapsed lungs. “My thoughts are crowded with death / and it draws so oddly on the sexual / that I am confused,” Gunn reflects. But it’s the lack of confusion – the clarity and orderliness – that really strikes you. He reports as if from a war front, like an Owen or Sassoon, offering anthems for doomed youth. But he doesn’t allow pity to disrupt his couplets and quatrains. “The friends surrounding me fall sick, grown thin / And drop away,” he writes. “Their deaths have left me less defined.” But his poetry keeps its shape and definition: he owes it to those friends to commemorate them with love and dignity. That tension between passion and constraint – which Gunn maintained right up till his death in 2004 – still sends shivers down the spine.

Read ‘Well Dennis O’Grady’, a poem from The Man With Night Sweats by Thom Gunn

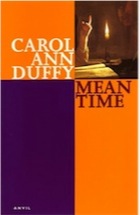

Gillian Clarke on Mean Time by Carol Ann Duffy, 1993

It was all there, already, in 1993: the energy of the syntax, the let and go of the iambs, the ear and eye for detail which so precisely captures a time, a place, a class. It is poetry driven by the fizz of being alive, the language bold and slangy. Yet we’re stopped in the headlong rush of words by the punctuation of a perfectly observed detail, a sudden tenderness – the saucer of rain in the garden, and the onion, “a moon in brown paper”, “the careful undressing of love”. And those clipped, sometimes aggressive last lines: “Fuck off. / Worship”. And “The taste of soap”.

Mean Time gave us some of Carol Ann Duffy’s best-known poems: “Valentine”, quoted above, “Havisham”, poems of childhood such as “Litany”, “Stafford Afternoons” and the loving, lovely poem for her mother, “Before You Were Mine”. Here are poems of her child self, the secretive teenage language of her adolescent self, the private shiver of new love, and outspoken adult love, as in “Disgrace”, all voicing her own and therefore the reader’s experience. Here too is her talent for classically iambic rhythms: a perfectly tuned, broken beat that sounds in ordinary speech to this day, and out of which Duffy makes great poetry. Daringly, after so much brash, bold language, the book concludes with a poem that has become one of the nation’s favourites, a perfect sonnet, “Prayer”. The poem and the book end thus: “Darkness outside. Inside the radio’s prayer. / Rockall. Malin. Dogger. Finisterre.” This worthy winner stays in the mind, as poetry should.

Read ‘Mean Time’, a poem from Mean Time by Carol Ann Duffy

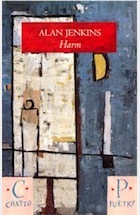

John Fuller on Harm by Alan Jenkins, 1994

Prizes encourage a firework metaphor of fame that distracts from the maturing of talent. Alan Jenkins’s achievement is in one sense classically starry: the launch with In the Hot-House (1988), soaring with Greenheart (1990) and bursting with the Forward-winning Harm (1994). Harm was a timely winner. It significantly mines the new vein of confessionalism available to poets schooled in the Lowell/Hamilton mode who had moved into a postmodernist playfulness. Jenkins explores self-abasement in a fictive world, with cock-and-bull adventures, dream-poems and Muldoonian rhyming (“Studebaker”/”rutabaga”) but also takes a circumstantial journey into remembered lust, shame and regret. The classic Jenkins scenario is the love-loss for which he has only himself to blame (“Houseboy”, “Bathtimes”). His poetry is what all poetry should be, the surprising and beautiful organisation of things that life has disorganised: “Missing, believed lost, five feet four-and-a-half / of warm girl, of freckled skin and sulky laugh / and blood on the sheets and ash on the pillow / with the smell of bacon eggs and lubricant …” (“Missing”)

The Drift (2000) and A Shorter Life (2005) consolidated the bright display, developing other themes of family guilt, childhood and the cruelty at the heart of thoughtlessness. And earlier this year the wonderful Hardyesque “Death of the Moth” was published. Certainly no falling off. The consistency and deepening of Jenkins’s achievement would be well served by a Collected: its resourceful variety now needs to be seen in extended form.

Read ‘Thirty Five’, a poem from Harm by Alan Jenkins

Paul Farley on Ghost Train by Sean O’Brien, 1995

A few months ago, I was giving a poetry reading in a small town in Norway with Stig Inge Bjørnebye (ex-Liverpool left back), sipping fiery aquavit. Which sounds like the staging of a notional Sean O’Brien poem. I’d taken an actual one with me, about football, that I thought they’d enjoy. They did. Flying home, I had a chance to rediscover the book this poem appeared in – Ghost Train – somewhere over the North Sea.

Had I forgotten the excitement of reading O’Brien in 1995? Perhaps subsequent work had occluded it: the two collections that followed Ghost Train were also strong; Downriver (2001) and The Drowned Book (2007) also won the Forward Best Collection prize. Reading this book again, I remembered how I’d sensed this secret history of the everyday being opened up, and being drawn to that dimension of his work. He was unmistakeable, entirely distinct even then, but there was definitely a faint background buzz of other writers whose work had ignited his: Douglas Dunn, Peter Didsbury, Roy Fisher.

Since Ghost Train, his work’s become part of the landscape, admired for its formal and imaginative confidence, by turns witty, angry, bold, virtuosic, audacious even. But on that plane I was reminded that this is also a writer with great resources of delicacy and mystery. I think of O’Brien as a poet of echoing corridors and northern rain and estuaries, of sidings and fireweed, in-between places and waiting and the silences that go on without us, of an England in its long afterwards, and what he once described as “the blue light and derelict happiness.”

Read ‘Revenants’, a poem from Ghost Train by Sean O’Brien

Read ‘Indian Summer’, a poem from Downriver by Sean O’Brien

Read ‘Eating the Salmon of Knowledge from Tins’, from The Drowned Book by Sean O’Brien

Alan Hollinghurst on Stones and Fires by John Fuller, 1996

John Fuller could justly have won the Forward in a number of other years, but Stones and Fires was an especially rich and involving collection. Much of it is elegiac in tone – opening with a poem in memory of the Oxford historian Angus Macintyre, killed in a motor accident, and closing with the wonderful “Star-Gazing”, an extended nocturnal reflection on mortality, grief and our place in the universe. Roy Fuller, the poet’s poet father, had died in 1991, and “A Cuclshoc”, though not strictly an elegy, is a heartbreaking record of two separations: the grieving poet finds a letter about a shuttlecock written to his father, absent in the Navy, when he was a small boy – “laborious sentences / With all their childish feeling and now with all / My later tears. I HOP YOU WILL COM BACK SOON // SO WE CAN HAVE SOME FUN.” The lobbed shuttlecock itself “glints / With the stitching of the angels, buoyant in the light, / Never falling.” Alongside such pieces Fuller set quite different things that showed him at the full stretch of his versatility – surreal experiments, a menacing blues on the brands of barbed wire, cryptic poems in prose. And luminous, humorous poems on Corsica, an island explored ever more hauntingly in several subsequent collections.

Read ‘Detective Story’, a poem from Stones and Fire by John Fuller

Kate Clanchy on The Marble Fly by Jamie McKendrick, 1997

The Marble Fly in question is carved, “a shade larger than lifesize / and much stiller than life and harder” on a wall relief in Pompeii. It is just one of a series of peculiar objects, from the skull of a Xhosa warrior, complete with bullethole, to the tiny spring from the inside of a biro, which Jamie McKendrick lifts and holds to the light in this spaciously paced but densely packed collection. The poems have diffident openings, self-deprecating endings, and, in the middle, tidal waves and centuries of violence. Somehow, the objects, and the poet, survive the disaster and carry on existing, modestly surprised.

This is a book like a cabinet of curiosities, one with fold-out shelves and a battered exterior. The agave plant and banana boat bristle from its pages as cleanly as they ever did, but you can’t buy the actual blue and black book with its modest, dated fly image any more. I cherish mine. It may even be worth something, for this collection was one of the last productions of OUP’s poetry list, a ship which went down, in true McKendrick style, sometime ago for reasons no one can now remember, in a year that began “with baleful auguries” and ended “fraught with the fear of war”.

Read ‘Gainful Employment’, a poem from The Marble Fly by Jamie McKendrick

Jeanette Winterson on Birthday Letters by Ted Hughes, 1998

A poem is a practical act of memory. When most memory is outsourced to hard drive and smartphone, the poem releases in the reader a private memory-store, prompted but not prescribed by the poem. This is a relief. Ted Hughes’s love affair with Sylvia Plath began with poetry and at the end of his life he took it back there. Birthday Letters was a supreme act of memory – faithful in the way that memory must be – in that it is partly invented. Hughes, the steady observer of the real, understood the quantum rule that the observer acts upon/alters what is observed, even if the observer is unobserved. That is exactly what happens in Hughes’s first famous poem “The Thought-Fox” (1957). In Birthday Letters, remembering Sylvia becomes the opposite of the dismembering of Sylvia that happened after her death; the poet parcelled out to satisfy a hunger for wreck, victim, blame, martyr. Pieces of Sylvia Plath fed rumour and gossip from the second of her suicide.

It was brave of Hughes to make public what had been private – the yearly conversation on the anniversary of her death. Time is not an arrow. Poetry disarms the clichés. Birthday Letters disarmed the commonplaces of death and loss. Love – and language – survive.

Read ‘Epiphany’, a poem from Birthday Letters by Ted Hughes

Daljit Nagra on My Life Asleep by Jo Shapcott, 1999

Shapcott is as rare as Eliot, Larkin or Bishop: each collection is long awaited and each poem has the weight of a novel with a unique unearthly mood. In “Motherland”, she says, “I am blue, bluer than water / I am nothing”; her personality is as diffuse and as uprooted as Bishop’s. This nothingness echoes the objective correlative of Eliot and enables Shapcott’s transmutation. She becomes in turn Thetis, cheetah, mad cow, quark (yes, quark!) and Mrs Noah, among others.

Coming to My Life Asleep, the reader may find the kind of horror that begets laughter as in Charles Simic or Goya, but they may also find the earned celebratory tone of Czesław Miłosz. Some of the poems seem to take their licence from Plath’s mushrooms, though Shapcott’s speakers are much livelier and weirder. Shapcott has the quotidian concerns of Larkin, as in a recipe poem about “Mandrake Pie”. The mandrake is best pulled at dawn, for the “double root / [is] said to have grown from seeds of murderers put to death”. Here we are given a gothic twist to dramatise a woman’s maddening servitude. Sometimes the poems feel as though they could be from the routines and imaginings of the unhinged subject of Charlotte Mew’s great poem “The Farmer’s Bride”.

Shapcott renews us by giving a fresh and affectionate perspective on the world. Consider her thoughts on the northern lights: “I have stolen / some of the light which drenches you this midnight / to wish you all the islands in the world / and every one a different kind of peace.”

Read ‘My Life Asleep’, a poem from My Life Asleep by Jo Shapcott

Don Paterson on Conjure by Michael Donaghy, 2000

When Conjure won the Forward, it was quickly declared to be “a genuinely popular choice”. This, for once, was true – though mostly because people found it difficult to begrudge Donaghy anything. His was a civilising influence on our excitable little constituency, and he was the first to remind us that all so-called “poetry wars” were really a knife-fight in a phone box. (Lord, have we missed him recently.) His poetry served much the same function. Through his example, our own poems took more pride in their appearance, showed greater respect for the reader, and understood the value of good humour. But Donaghy’s great gift was his ability to forge a poetic language where thought was indivisible from feeling.

Donaghy was a slow worker, and really only wrote one book, which he published in instalments. There were no particularly noticeable developments of either technique or subject matter; the former had always been seamless enough to be largely invisible, and his interests were so eclectic, nothing so base as a “theme” would ever emerge anyway. Conjure is the third part of the glorious tetralogy that ended with the posthumous Safest a few years later. It has eight or 10 poems that are among his very best: “Caliban’s Books”, “Haunts”, “Our Life Stories”, “Black Ice and Rain” … All accomplish the Donaghy trick of hitting you simultaneously in the solar plexus and between the eyes; every rereading reveals an unsuspected layer of complexity, allusion and – I realise belatedly – moral subtlety. “Tears” is short enough to quote in full, which is the only way one should ever quote these marvellous poems: “Tears / are shed, and every day / workers recover / the bloated cadavers / of lovers or lover / who drown in cars this way. / And they crowbar the door / and ordinary stories pour, / furl, crash, and spill downhill – / as water will – not orient, / nor sparkling, but still”.

Read ‘Caliban’s Books’, a poem from Conjure by Michael Donaghy

John Kinsella on Max Is Missing by Peter Porter, 2002

Max Is Missing is a vibrant, philosophically flexible reinvention of poetic persona that takes Porter’s renowned wit, and knowledge of European history and cultural arts, further into his varied equivocations over the meaning of Nature (with a capital N). Porter’s comparisons come down to moments or examples of human achievement and failure. He brings the “urban mind” into confrontation with any “Wordsworthian” tendencies that might raise their head, if with irony. Max offers room for animals, not only as poetic device, but also as creatures in themselves, even if the forces of existence weigh them down. Porter’s confrontation of Nature’s contradictions comes out of a Hardyesque fatalism more than an epiphany. His world is both God-filled and Godless; when God does appear it is often with a bleakly indifferent supremacy. While the classical wrestles with the modern (so often found wanting), there’s a lightness that retains satirical depth while inviting familiarity, gossip among the hard-edged reasoning, and the ability to poke fun at himself and his subject: “We who would probably want to remake / or at least tidy up Tracey Emin’s bed”. There are a handful of poems on Australian subjects. “Duetting with Dorothea”, referring to the author of one of Australia’s best-known (though least “great”) poems, laments: “Instead I saw a landscape / Lit up by inner doubt.” And in a colonised space, this is surely a legitimate stance for a non-indigenous Australian. One should always have doubt.

Read ‘Last Words’, a poem from Max Is Missing by Peter Porter

Kathleen Jamie on Breaking News by Ciaran Carson, 2003

Kathleen Jamie on Breaking News by Ciaran Carson, 2003

I loved Breaking News because of all the white space, because the poems were sculpted out of silence. It’s not a quiet book, however: it’s about war and terror. The loud painting on the cover – Géricault’s The Blacksmith‘s Signboard – sets out the book’s concerns. Géricault and Goya could be considered the war photographers of their day, and both feature in Breaking News, because war and its wastes are ever with us.

Carson’s interest in the Crimean war in particular was quickened because many streets in his native Belfast are named after Crimean battles, so the book refers back and forth, from Belfast to Balaclava with surveillance helicopters, bomb alerts and the wretched warhorses. The poised spare poems, many with just one word to a line, are perfect, and take their bearings from William Carlos Williams (imagine his Red Wheelbarrow abandoned on a battlefield) – a debt Carson acknowledges.

But he can’t resist opulent language for long. The closing section of the book is called “The War Correspondent”, and this, as Carson’s notes say, owes much to the Anglo-Irish journalist William Howard Russell, whose vivid dispatches shaped attitudes to the Crimean war. In a remarkable series Carson’s skilled work with line and rhythm turns those dispatches, sometimes verbatim, into poems of richness and depth. It’s a book that bears witness to horrors past and present, and shows that poetry inhabits our streets and newspapers, and that in talking about the disasters of war one can still call upon language which is now clean and bone-like, now rich and honeyed.

Read Gallipoli, a poem from Breaking News by Ciaran Carson

Jo Shapcott on The Tree House by Kathleen Jamie, 2004

I first read The Tree House when it came out in the autumn of 2004. I dived into poem after poem, thrilled: it was one of those books that announces a change in the temperature and direction of poetry, a real breakthough on behalf of the whole art. It is not only that the poems teem with living things and are fresh and delicate, beautifully made. Or that their sound world, enhanced by Jamie’s deft use of Scots in some poems, is a treat for the ear. The Tree House looks again at the way humans live in and with nature; how the natural world penetrates thought; how we understand and react to living things. The poems explore the human contradiction of feeling separate from nature but actually being part of it. More than that, they are both profound and oddly practical in proposing how we might make our way through the world. Perception, a morality of looking, is part of it: “what could one do but watch” asks the narrator in “The Basking Shark”. One of my (many) favourite poems, “Flight of Birds”, is elegiac, a tone which threads through the book and which is all too appropriate in the face of our destructive impact on the Earth. “We’ve humiliated living creatures,” says the narrator. She goes on to ask, almost tentatively, “might we yet prevail / upon wren, water rail, tiny anointed goldcrest / to remain within our sentience in this, / the only world?” I remain grateful for this book; in awe.

Read ‘Flight of Birds’, a poem from The Tree House by Kathleen Jamie

John Burnside on Legion by David Harsent, 2005

When I read poetry, I am looking for a world that I could never have imagined for myself. A worldview, a sensibility, that begins by seeming strange, even alien, but ends up leading me, sometimes reluctantly, into a suddenly familiar territory of ancient memories and repressed dreams. This is the territory where Blake receives his visions of Albion, but also where Baudelaire lurks in the smoky, perfumed shadows; Wallace Stevens pursues the as-if of the supreme fiction; Marianne Moore builds her astonishing menageries and imaginary gardens with real toads in them. Though, as Mandelstam says, we should not compare – “the living are beyond comparison” – I’d have no hesitation in adding David Harsent to that list, for his is probably the richest, most seductive and, at the same time, most rigorous imagination working in English poetry today, and Legion is a tour de force of subtle music, unsettling imagery, unmatched formal agility and a worldview that is, by turns, a joy or a terror to share.

I often recommend, to friends, students and outsiders fresh to English poetry, the haunting, beautiful and deeply unsettling “Ghost Archaeology” as an example of the best of what is happening in contemporary writing. As close as any finished thing comes to perfection, this is work of subtle, yet gently insistent musicality, compassionate in the true sense of the word and, as it reaches its eerie closing lines, deeply humane in its vision. This is poetry of utter integrity that, for the attentive reader, can make the world, if not a better, then at least a truer place.

Read ‘Arena’, a poem from Legion by David Harsent

David Harsent on Swithering by Robin Robertson, 2006

Robin Robertson’s vision is compelling, dark, unmistakeable. In Swithering, the developmental side of vision is everywhere evident: two poems that take Strindberg as their subject are subtly referential in their narrative continuity; “Ghost of a Garden” and “A Seagull Murmur” come at personal loss in different ways, though both have about them a sort of steely tenderness; and “Selkie” finds a new aspect in a later poem, “At Roane Head”, which won the Forward Best Single Poem prize in 2009.

For me, though, the most telling linkage in the book comes with the two approaches to the Acteon myth: a brilliantly turned version of Ovid, and a broken narrative titled “Acteon: The Early Years”. In the former, the story of Acteon’s transformation by Artemis and the terror and savagery of his death is given in tense, flexible free verse. The poem as a whole, but especially the passage that describes the hunt, is unrelenting and fierce and almost filmic in its intensity. The latter seems to me one of the most affecting poems Robertson has written – but also unrelenting, also fierce. The way it converts the Acteon narrative to its own purpose – a haunting and painful form of unrequited love informing a loss of innocence – is unsparing and unforgiving. I hope I might provoke readers to go to the poem if I say that the moment of bitter resolution in the final section is both startling and deeply moving.

Read ‘A Seagull Murmur’, a poem from Swithering by Robin Robertson

Andrew Motion on The Lost Leader by Mick Imlah, 2008

The Lost Leader was Mick Imlah‘s second collection: it came out 20 years after his first, Birthmarks, and a few months before his death from motor neurone disease. The tragedy of that early death still feels so intense, it’s difficult to read The Lost Leader without feeling our responses to the poems are in various ways pointed and shaped by our knowledge that they are the last Imlah wrote. He is not au fond a Keatsian poet, but his legacy is tinged with a Keatsian pathos.

Imlah’s first book had shown in some parts an aptitude for ventriloquism (especially of 19th-century voices), and in others for a beautifully calm form of documentary lyricism; in his later work both these things are refined in the service of a loosely structured narrative that gives “the matter of Scotland”. Sometimes the concentration is on major historical figures such as Bonnie Prince Charlie. Sometimes it is on out-of-the-way things. In every case the forms are ingenious but sturdy, while the voice that delivers them is soaked in the tradition, but utterly original.

In later parts of the book, Imlah looks more directly at his personal history. For first-time readers, these are likely to seem the most welcoming – especially the very witty but tender poems to his wife, and those about his children and contemporaries. In one of these, the elegy for his university friend Stephen Boyd (like Imlah himself, a keen rugby player), he says “sport matters / Because it does not matter”. In a qualified sense, this assertion takes us close to the heart of everything Imlah achieved as a writer. He is absolutely serious, and often concerned with grave subjects, but entirely without self- importance. The Lost Leader was certainly the best poetry book published in 2008; one of the best poetry books of the new century, in fact.

Read ‘Maren’, a poem from The Lost Leader by Mick Imlah

Ian Duhig on Rain by Don Paterson, 2009

Paterson is one of the essential contemporary poets of these islands; formally accomplished and inventive with a pitch-perfect musician’s ear. His work has never been short of that playful ingenuity so ubiquitous a feature of modern poets’ lockers – and of which modern readers sometimes weary. Rain, for me, moved his writing beyond “all the craft and clever-clever” (the charge levelled against himself in his earlier Landing Light), and the reasons for this were brutally clear: it wasn’t a matter of technical development – rhymes are unshowy here, rhythms depressed – but the acquisition of pain. The “clever-clever” is still occasionally present, as in his techno-geekfest “Song for Natalie ‘Tusja’ Beridze”, but the author of God’s Gift to Women always knew he wasn’t, and throughout the doubting, self-interrogating collection, poems of heartbreak are made from fragments of hearts other than Paterson’s: “‘You’re saying that because / the bed’s a light-year wide, or might as well be, / I’m even lonelier than I thought I was …'” (“The Day”). His earlier sex poems would detumesce beside those here on parenthood or, crushingly, abortive parenthood (in “The Swing”). Haunted by loss, Rain is dedicated to the memory of Paterson’s great friend, that other fine poet Mike Donaghy, dedicatee of its longest poem “Phantom”, where Donaghy’s ghost admits “I loved the living but I hated life”, painfully true of many poets’ self-regarding attachments. One critic wrote that Rain‘s success restores faith in prizes. Perhaps, but it’s a book of broken faiths.

Read ‘The Swing’, a poem from Rain by Don Paterson

Nick Laird on Human Chain by Seamus Heaney, 2010

In Kuno Meyer‘s translation of the ninth-century Triads of Ireland, “the three glories of speech” are rendered as “steadiness, wisdom, brevity”, and that trinity might serve as a précis for Heaney’s work. Human Chain, though, sees that Heaney steadiness, the sense of balance and endurance, undercut by a new tenor of instability and uncertainty: the poems were written after a mild stroke Heaney suffered in 2006 and, while not comfortless, they come to doubt “the solid ground”: “As I age and blank on names, / As my uncertainty on stairs / Is more and more the lightheadedness // Of a cabin boy’s first time on the rigging, / As the memorable bottoms out / Into the irretrievable, // It’s not that I can’t imagine still / That slight untoward rupture and world-tilt / As a wind freshened and the anchor weighed.”

Heaney’s late style has gravitated towards the relaxed line, and there’s a conversational freshness to these pieces. The vernacular idiom is mixed with the lapidary though, just as the poems integrate the local with the classical. Meditating on mortality makes time contract and bend; gaps between the past and present disappear as death begins to press its pattern over every life. These poems, which include many great elegies to friends, move “among shades and shadows stirring on the brink”, ghostly parents and grandparents and first loves.

Human Chain is Heaney’s Book of the Dead, and sits easily among his finest collections. Though revolving around sadness and loss, the book continually finds the energy and imagery to make looking over the last threshold possible. In his elegy for David Hammond , Heaney sees himself at his friend’s open door: “I felt, for the first time there and then, a stranger, / Intruder almost, wanting to take flight // Yet well aware that here there was no danger, / Only withdrawal, a not unwelcoming / Emptiness, as in a midnight hangar // On an overgrown airfield in late summer.”

Read ‘Had I not been awake’, a poem from Human Chain by Seamus Heaney

Fiona Sampson on Black Cat Bone by John Burnside, 2011

John Burnside creates a world of tones and shifting, shifty meanings that’s not quite like anywhere else. But it resembles the secret, often rather shameful, world of our own hopes and fears. This is particularly true of his poetry, which frequently evokes the dreamlike sensation of blundering through a landscape that is on the brink of offering him, or us, an extraordinary revelation.

The evocation itself, though, is done with exceptional subtlety. Black Cat Bone, Burnside’s 12th collection, brings together his narrative and musical gifts in a way that echoes and develops all that has come before. In the long opening poem, “The Fair Chase”, part ballad and part folk tale, the protagonist is a sort of holy fool, “flycatcher, dreamer, dolt, / companion to no one, / alone in a havoc of signs”, who follows the hunting traditions of family and community, and “becomes / the thing he kills”. This kind of transubstantiation isn’t new in Burnside’s work. His characteristic chain-link imagery passes images forward to create whole landscapes. But, here, that dream logic echoes a kind of “phantom narrative” in other poems, such as “Faith” and “Notes Towards an Ending”, which seem to tell stories from the world of relationships – but don’t do anything quite so reductive.

And all this in Burnside’s extraordinary music. His long sentences, his tumbling scenes and details, add something quite new to the English lyric tradition: the chance to riff, a kind of trance-like rapture. It’s for this sound, as much as for his wild delicacy, that Burnside evokes such passionate admiration.

Read ‘Notes Towards an Ending’, a poem from Black Cat Bone by John Burnside

guardian.co.uk, Thursday 6 October 2011